Rust Lang Book - Chapter 3 Notes

Last updated:

This is the third blog post in my Rust Ultralearning series. In my first post, I highlighted my study plan and notes on Chapter 1 of the Rust Lang Book. The second post covered my notes on Chapter 2. Here, I cover my notes on Chapter 3.

Notes on Chapter 3

In this chapter, we learn common programming concepts in Rust. This chapter covers the following:

- Variables and Mutability

- Data Types

- Functions

- Comments

- Control Flow

Below, I’ve broken up the different topics and points that I highlighted from this chapter:

guaranteed safety

In Rust, the compiler guarantees that when you state that a value won’t change, it really won’t change.

Thanks to the compiler being strict, you can guarantee that your variables won’t be mutated. It’s only possible for them to change if you mark them as mutable.

constants vs variables

In Rust, there is a keyword const and no, it is not your JavaScript const. They are values that cannot be mutated. Things to remember about const:

- Can’t use the

mutkeyword - Type has to be annotated

- Value must be known at compile time1

Sounds like they are good for values that are never going to change, like your birthday:

const MY_BIRTHDAY: &str = “01/11”;I found these examples from the docs for const helpful.

redeclaring vs shadowing a variable

I may write a whole blog post about shadowing variables. The Feynman technique would come in handy for this topic. Here is an example from the book:

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let x = x + 1;

let x = x * 2;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

// This prints out “The value of x is: 12”

}They say,

By using let, we can perform a few transformations on a value but have the variable be immutable after those transformations have been completed.

I think here I felt caught up on the difference between redeclaring and shadowing. Declaring a variable looks like let day = “Friday”. Redeclaring in my mind is using the same name and changing the value within the same scope. I think that’s the same as shadowing:

fn main() {

let day = “Friday”;

let day = “Saturday”;

println!("The day of the week is {}", day);

// prints out “The day of the week is Saturday”

}I may come back and update this after further investigation.

integers - should I care about bit length?

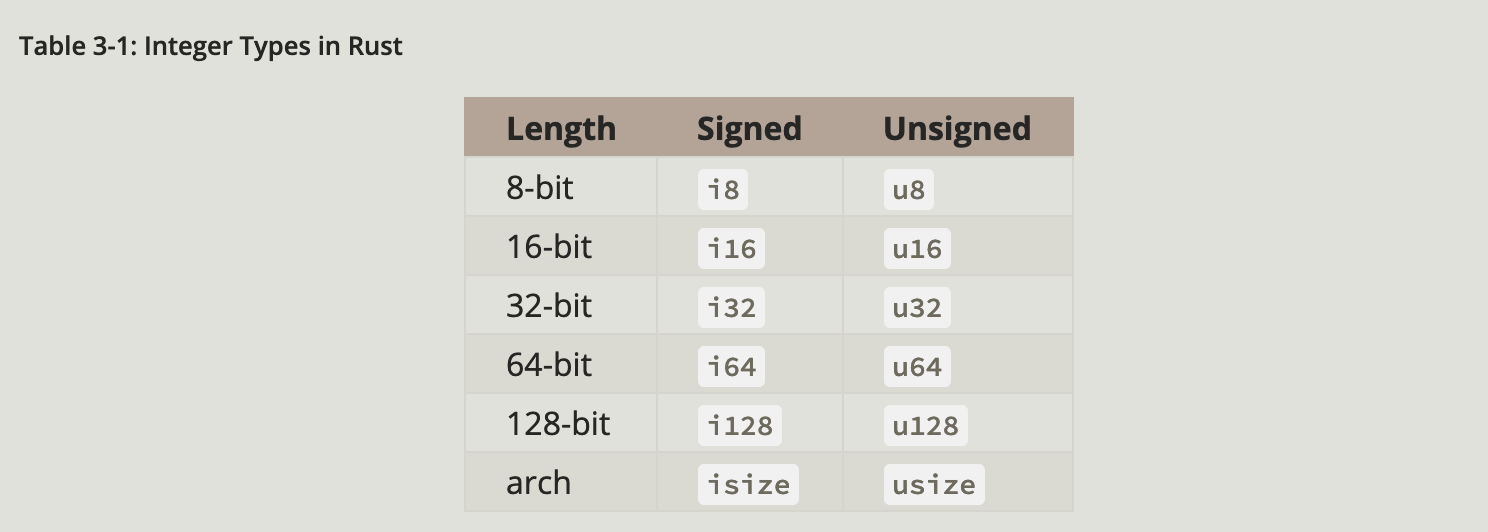

In the “Integer Types” section, they show a table of the different integer types in Rust.

I am not used to worrying about the bit length. Do I need to worry about it?

I don’t know the answer yet, but I’m sure I will find out as I learn more. One thing they said,

If you’re unsure, Rust’s defaults are generally good choices, and integer types default to

i32: this type is generally the fastest, even on 64-bit systems. The primary situation in which you’d useisizeorusizeis when indexing some sort of collection.

I’ll probably forget so we’ll summarize by saying:

- Use

i32if you’re unsure - Use

isizeorusizewhen indexing a collection

isize and usize

I feel like the docs didn’t explain these beyond “they exist.” They did say this,

Additionally, the isize and usize types depend on the kind of computer your program is running on: 64 bits if you’re on a 64-bit architecture and 32 bits if you’re on a 32-bit architecture.

Beyond that, I’m leaving a note for myself here that I may need to come back and dive deeper.

decimal, hex, octal, binary, byte

All of these can be written as number literals! That’s cool, I think. Apparently, you can do this in JavaScript too. I can’t think of a situation where I’ve wanted one of these literals, but I know they exist. Again, something else I may come back to.

_ can help with readability

Similar to TypeScript, the _ can be used as a numeric separator. Here are a few examples

10_0001_000_000.123_45610_000.01

My colleague Jeremy described it really well:

_ is equivalent to using , when writing long numbers in English (eg 1,000,000.123456). In English you wouldn’t use , after the decimal point, but you can use _ there in Rust (eg 1_000_000.123_456).

integers - so much to learn

In my notes I wrote “too many integers”, but what I meant was “there is so much to learn about integers.” I’m sure in practice it’s less than. Everything was designed for a reason. Although the reasons are not yet clear to me, I assume it will make sense down the road.

checking for integer overflow

Rust can check for integer overflow. There’s one caveat - it only checks in certain modes. What do I mean? Well, tell me the mode in which you compile your code and I’ll tell you if it checks.

- Debug mode? YES

- Release mode? NO

Remind me again, how do I know which mode I’m compiling in? Well, I’ll answer a question with a question - did you pass the --release flag? No, then you’re probably compiling in debug mode. Otherwise, if you did, you’re in release mode. Something to keep in mind.

floating points are numbers with decimals

There are two primitive types: f32 and f64. I learned that the default is f64 because

…on modern CPUs it’s roughly the same speed as f32 but is capable of more precision.

Other things to note:

f32has single-precisionf64has double-precision

A question I have is, “what’s the difference between single-precision and double-precision?” I may explore this down the road.

” for string literals and ’ for char literals

Finally! A decision made for me so that I don’t have to choose. I also don’t have to debate about which is better. In JavaScript, I can use either single or double-quotes. Here in Rust, you use single for char literals and double-quotes for string literals. Woohoo!

arrays vs tuples

Both have fixed lengths. The main difference is the syntax and the fact that arrays must have the same value. Here are some examples:

// This is a tuple.

// It uses ()

let my_cool_tuple = (1, “hello”, 10);

// This is an array

// It uses []

let my_cool_array = [“This”, “only”, “has”, “strings”];When should you use arrays over tuples? Well, the book says,

Arrays are useful when you want your data allocated on the stack rather than the heap.

Stack? Heap? Hmm.. this is not something I’m used to as someone who worked primarily in JavaScript. Luckily, they say more is coming in Chapter 4.

you can destructure tuples

I like destructuring so I was happy to see this is a thing.

let my_fav_things = (“red”, “guacamole”, 21);

let (fav_color, fav_food, fav_num) = my_fav_thingsvectors vs arrays

Since arrays and tuples have fixed lengths, what do I use if I don’t know how big or small of a collection I’m working with? That’s where vectors come in! Unlike arrays, vectors are allowed to shrink or grow. The question then is, why not always use vectors? I’m guessing there are benefits to each. Vectors are discussed more in-depth in Chapter 8.

stack or heap - should I care where I am allocating memory?

I wrote this question down for myself while reading this chapter. I’m not super familiar with memory allocation or worrying about the stack/heap. I assume the next chapter will discuss this. Noting here so I don’t forget.

Rust checks for array index bounds

I’ve run into this issue in JavaScript where I go beyond the bounds of an array’s indices. Luckily, Rust has our back. The authors say,

In many low-level languages, this kind of check is not done, and when you provide an incorrect index, invalid memory can be accessed. Rust protects you against this kind of error by immediately exiting instead of allowing the memory access and continuing.

Good to know Rust is on our side.

snake_case and Rust - it’s official

Rust code uses snake case as the conventional style for function and variable names. I knew it! In my first post, I guessed this might be the case. Glad to have validation.

functions are hoisted

Hoisting functions in JavaScript means you can write a function that uses a function you have yet to define. Rust lets you do the same thing! As the author puts it,

Rust doesn’t care where you define your functions, only that they’re defined somewhere.

Woot woot!

function signatures require type annotations

Similar to TypeScript, Rust requires you to annotate your function signatures.

// Borrowed from the Rust Lang Book

fn another_function(x: i32, y: i32) {

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

println!("The value of y is: {}", y);

}implicit returns in functions

Implicit vs explicit returns in JavaScript confused me for a long time. With arrow functions, you get implicit returns

const addOne = (x) => x + 1;Well in Rust you achieve something similar. Here is an example:

fn five() -> i32 {

5

}Worthwhile to remember:

In Rust, the return value of the function is synonymous with the value of the final expression in the block of the body of a function.

semicolons change expressions to statements

One thing to keep in mind is that semicolons at the end of expressions turn them into statements. Expressions evaluate to values, but statements don’t. Confusing? Let’s look at an example:

fn plus_one(x: i32) -> i32 {

x + 1

}Here, there is no semicolon in the x + 1 line. This means it’s an expression. And remembering what we said above, expressions evaluate to values. This works. However, as soon as we add a semicolon to the x + 1, the compiler gets upset.

Why? Well, now our expression is a statement. And the statement’s type is now (), but it should be i32. We can fix that by changing x + 1; to return x + 1;. The moral of the story: these two functions return the same thing:

// Using an expression

fn plus_one(x: i32) -> i32 {

x + 1

}

// Using a statement

fn plus_one_version_2(x: i32) -> i32 {

return x + 1;

}if expressions sometimes called “arms”

We learned previously that match expressions are made up of “arms”. Well if expressions are also called “arms”. Like humans, Rust has two arms - woo!

conditions in if statements must be Booleans

Unlike in JavaScript where values in if statements are coerced, Rust only lets you use Boolean expressions.

lots of if/else statements? Use a match

This is a friendly reminder from the book. If you find yourself working with lots of else if statements in your Rust program, reach for a match expression

three loops: loop, while and for

Previously, we had only touched the loop kind of loop. Now, we know there are two others.

loop: runs forever, unless you use abreakwhile: checks a condition before runningfor: iterating over a collection of things (also most commonly used loop construct)

break can return values

This delighted me! The break statement can return values inside your loop. Check out this example from the book:

fn main() {

let mut counter = 0;

let result = loop {

counter += 1;

if counter == 10 {

break counter * 2;

}

};

println!("The result is {}", result);

}Two things to notice here:

- The loop is assigned to the variable

result- I didn’t know assigning loops to variables was a thing! - The

breakreturns the value for the expressioncounter * 2- how cool is that?

Practice, practice, practice

This chapter felt like the heaviest of the three I’ve read thus far. At the end, the authors suggest building the following programs to practice:

- Convert temperatures between Fahrenheit and Celsius.

- Generate the nth Fibonacci number.

- Print the lyrics to the Christmas carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” taking advantage of the repetition in the song.

I haven’t done this yet, but I’m writing it down so I won’t forget. None of this will sink in unless I practice!

If you build any of these programs, let me know! I’d love to see them.

What’s next?

Next up in my learning plan, I will contribute to an open-source project. The goal is to find something within a Rust codebase that is beginner-friendly. This might be a bugfix or an update to documentation. Half the battle is navigating a new codebase in a new language, hence why I’m aiming to start with something small.

I have a few projects in mind (thanks to friends on Twitter for your suggestions!). I haven’t picked one yet, but I will share it once I do.

Even though it wasn’t part of the original plan, I’ll write up a short post about my experience afterward. Until then, happy coding my fellow Rustaceans! 🦀

Following the pattern of the last post, I included a glossary and cheatsheet at the end here. I hope it helps!

Glossary

I find it helpful to define new terms when I learn them. Here they are in my own words:

- argument - concrete values provided to your function when you call it

- arm - a branch of code (i.e. one option out of more than one)

- ASCII - character encoding standard

- binary - number expressed in base-2

- byte - unit of information, usually consisting of eight bits

- compile-time error - happens in development mode, the compiler is upset

- compound type - a group of multiple values into one (tuple, array, etc.)

- debug mode - compiling your mode for local development (TODO double check)

- decimal - a number with a fraction (not whole)

- floating-point type - a decimal number, but represented differently

- function signature - what you use to call your function

- hex - number expressed in base-16

- hosting - when functions are lifted to the top of the scope

- integer - a number without a fractional component (whole number)

- integer overflow - number is bigger or smaller than it’s container

- keywords - reserved words for the use in that language (i.e. for in JavaScript, fn in Rust)

- numeric operation - addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and remainder

- octal - number expressed in base-8

- panicking - when your program exits unexpectedly

- parameters - special variables that are part of a function signature

- release mode - compiling your code for production (TODO double check)

- runtime error - happens while program is running, possibly in production

- scalar type - a single value such as integer, floating-point number, Boolean, and character

- signed integer - the number can be positive or negative (i.e. the sign matters)

- Unicode Scalar Value - a value that represents a character in unicode

- unsigned integer - a positive number without a fractional component

- 32-bit CPU - primary processor used in the ‘90s

- 64-bit CPU - more common processor used nowadays, can handle more data

Cheatsheet

Most of the commands that were covered in Chapter 3:

Write an array with the same value

// this is shorthand for an array of 5 elements

// equal to the value of 3

// i.e. let a = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3];

let a = [3; 5];Quit an infinite loop running in a terminal window

# same as with a Node application

# ctrl-c

^CThank you!

A special thank you to Cami Williams, Aaron Abramov, David Tolnay, Jeremy Fitzhardinge and Qingwei Lan for helping me understand some of the more difficult topics in this chapter!